Date: 28 November 2004

Location: Cafe Nero, Kingsway, London

EP = Ed Pinsent, PM = Patrick McGinley (ie murmer)

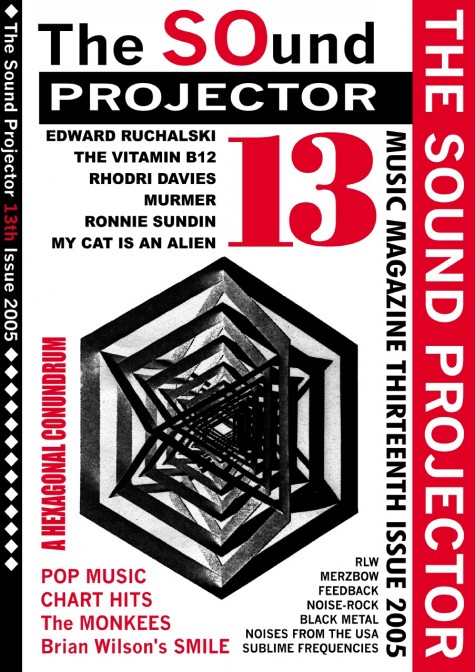

The Sound Projector #13, 2005

Ed Pinsent: When did you start getting into the electro-acoustic field?

Patrick McGinley: When I was in my mid-teens, I started listening to industrial music and things like that, and I think that took me through to always looking for music that was one step less musical in its construction.

EP: When you say Industrial, can you name some names?

PM: At the time, the big commercial industrial acts. Skinny Puppy and Ministry I was listening to, and those led me to Einstürzende Neubaten. You know, getting a little bit further away from the mainstream with each step. I mean, Ministry are basically a heavy metal band! And that led me from there into things like Zoviet France and that Spanish band – TGTV or something. Esplendico Geometrico. Still quite rhythmic. Brume, I found quite early on/ I just listened to that stuff for years. A lot of it was on cassettes, because I had to copy it from friends, I didn’t know where to buy any of it, but I managed to find quite a few people on my University campus who made copies for me and then I slowly started to find ways [to buy it]. I found Soleilmoon first I think. Then when I moved to Ireland, for some reason there were a couple of shops that actually had [these records] in the shop, which was quite a novelty. I used to find a lot of Zoviet France, and Controlled Bleeding, Asmus Tietchens records…for some reason, they stocked them all. There were two shops, and one of them was Tower Records! They must have had a guy working for them that was a fan. He kept it all himself. The other one was a small record store. I was quite lucky as far as discovering things.

EP: So you listened to all this industrial music. Were you ever a fan of what I would call the classical electro-acoustic, like Francois Bayle, Pierre Schaeffer, or Pierre Henry?

PM: Not until much later. Pierre Henry I didn’t really discover until I moved to France, which was only in 1996. I knew he existed but I hadn’t really listened to any of his stuff. Hadn’t looked into Schaeffer or any of the contemporary acousmatic school, Bayle and that lot. And even now I don’t listen to too much of that. I have listened to a lot of Schaeffer and Henri for historical education purposes.

EP: Did you discover Roger Doyle in Dublin?

PM: I did come across him, I think before I went to Dublin, through a friend. I looked around but I didn’t see a lot of his records there, and I never knew a lot about his work. I heard the long radio piece, Babel. I don’t think I’ve ever listened to it all the way through.

EP: How did you go from being a fan of this music to becoming a musician?

PM: I was always a musician as well in other schools, I think I knew that I wanted to…I can’t remember when the point came where I thought I might like to make this stuff, but I do remember the process of knowing that I wanted to start constructing sound-works, and wondering how and when I was going to be able to do it. And I remember it was quite a while between that thought, and when I actually got round to devising the means to start doing work. I remember walking around Paris specifically. I got there in 1996. Just hearing very specific – and I think this was my first links with field recording work that I ended up working with. Actually it wasn’t quite, but anyway…just hearing sounds, and thinking I’d really like to just find a way to capture that, and capture this, and just very simply construct things just from those. I wasn’t thinking about manipulation or anything. Just taking those sounds and layering them up. Somehow in my head they formed these bright, coherent and rhythmic structures.

EP: This was after taking a walk through Paris?

PM: Yes, I remember specifically wandering in front of a Government building that had these vents leading down into its bowels, right at street level. And I would walk by that, and there would be amazing sort of pulsing, breathing ventilation sounds pouring out of it. And I always thought I really wanted to record that. This was when I couldn’t be buying DAT recorders and this was before mini-discs, which was my eventual way in. It was before digital technology was affordable. I could have gone with a tape recorder, I suppose.

EP: So you knew what you wanted, in a way, in advance. You had this moment of epiphany almost.

PM: Yes, I knew what I wanted, and I just had to find a way to do it. It was the same thing as a fan of music. I remember thinking in my early discovery days, the moment when I suddenly realised that anything I could imagine wanting to hear – somebody had done! And if I looked hard enough, I could find it. And that’s what it was, in those stages. When I heard Zoviet France for the first time, it was – that’s exactly what I was looking for! What can I think of next? I started thinking about looking for things more heavily constructed out of real sounds. As I said before, that was probably my first conscious link to field recording work. Thinking that these sounds that we hear all the time and ignore, that’s what I want to hear in music. And then finding it!

EP: Interesting…in a way, it sounds like you’re saying your imagination was one step ahead of hearing the music. You imagined it existing, and then later on you went and discovered it, or at least found something that was a close match.

PM: Yes. It was always like a challenge. What can I go looking for next? And how long is it going to take me to find it? But the key was that it was always there. Somebody else had always thought of it first and done it.

EP: What form did your first experiments take?

PM: My very first experiments with sound were while I was in Paris in the context of my studies. I was studying theatre, which I had studied at University. But I was in Paris for two years to study physical theatre. We had an opportunity on several occasions to perform live sound for pieces, performance pieces that we were working on. And they tended to be acoustic instruments or percussion. Even the first ones I did were centred around traditional Irish instruments, whistles and percussion and bodhrán and spoons and things. But we had one project in our final year. The performance works we were working on were more abstracted, ethereal and mysterious. In that context, looking for live sound to accompany these performances, for the first time I started to join those works with the experimental music that I’d been listening to for years. So I borrowed a guitar amplifier and a delay pedal and a cheap clip-on tie mic, and started creating live sound-scapes just with instruments for these performances. And that was the first time I took steps towards linking those worlds for myself.

EP: It was quite a bold step to do it live in that way. Was it just you solo, or were there other people?

PM: It was just me. It was a big performance group, but I took myself out of the performances, for that performance. I didn’t appear on stage at all. I actually carved out a little backstage area for myself and set up tons of bowls of water and just bits of metal and the instruments, and percussion, and just this cheap mic. It was kind of comforting for me because I was – in those contexts, it’s usually very stressful to present yourself forward on stage, so it was kind of a nice little respite, after two years of theatre work. To just hide away and make these noises.

EP: Was there a narrative meaning to the performance, that you were trying to support with the sound, or was it quite abstract?

PM: It was basically a series of short pieces that the students would have come up with. There was work on melodramatic choruses, or tragic choruses like Greek choruses, but in modern contexts and with modern texts. And then something that they called The Mystères, which was unearthly constructions and beings and scenarios that were less narrative and more visceral. And it was those links specifically that I was able to add to, with sound. And also just to link all these small bits together into something of a more coherent whole as a show, as a performance.

EP: Because your sound would be running continuously, I assume, even though the performances were quite bitty…

PM: Yes, and as it would shift from one thing to another, the sound might shift. I also actually, now I remember, had a few live mics set up on stage to capture the sounds the performers were making. That was the feedback that I got anyway, that it was making the show into a coherent whole.

EP: Could you see what they were doing?

PM: I could…just about, from the wings. I put myself in a place where I could [see]. I was taking cues off them too. It wasn’t just a background soundtrack, it was all quite linked to the direct action on stage.

EP: What happened after that, did you start making some tape experiments?

PM: After those studies finished I moved to London and almost immediately one of the first things I did was buy a minidisc recorder. They’d just come on the market. And a small stereo mic. And that’s when, for the first time, I put this old – for me – the old idea into practice, of going around and capturing these sounds that I was hearing out in the street or wherever, and trying to work with those. Just with those, I had to borrow a cassette four-track and some borrowed effects pedals for guitars, and I started just experimenting with composing with those sounds. At the same time the reason I came to London was to work with people I’d studied with in Paris, to form a theatre company. So I was performing with that company but also composing the soundtracks for our shows. We did two shows in two years, the first one for which I did a pre-recorded soundtrack and the second one similar to the project I was talking about when I was at school in France, I performed live. This time I performed the soundtrack live on stage and acted a role, a sort of narrator role to the show as well. The sound objects were set up in a more aesthetic way. And that became part of the character as well, the manipulation of the space through sound. At the same time, all along with that, I was considering my work with these new [things]- my first steps in field recording that I was doing, and they were working their way into the shows.

EP: It seems that right from the start you intended to manipulate the field recordings that you were gathering…

PM: I think by the time I actually got the means to capture the recordings – yes, I was thinking towards manipulation. The first things I did were very loopy. Not rhythmic in a seried and musically rhythmic way, but just in the capture of small fragments of sound that I quite liked out of a less interesting recording. I would create a soundscape out of those small bits.

EP: This evolved over time into what you’re doing now, these quite sophisticated treatments of very long stretches of sound.

PM: Yes, I’ve moved away from the loops I suppose, or the short loops. I can still loop a few minutes of a recording just to carry on with a particular texture over time.

EP: In quite a short space of time you’ve evolved this quite coherent method of working.

PM: I guess so. I think it because I was, like you say, I had the ideas first before I had the means. So it was quite a natural progression to follow.

EP: With your work now, do you ever use the computer to process tapes?

PM: I’ve started using the computer for the first time ever, for my radio show (ie Framework on Resonance 104.4 FM in London). As of yet, I haven’t used it at all for any of my sound work. Although using it in my radio show I’m starting to see ways in which I might want to use it. I’ve sort of avoided it up till now. Not really out of a dogmatic hate of the laptop – probably partially out of that – but because up to now I’ve found that everything I’ve wanted to do I could do with what I have. I started with a four-track, I upgraded to an eight-track and a minidisc, which is now broken which is another reason that I might need to start using multi-tracking. I’ve gone from a cassette four-track and two guitar effects pedals to digital eight-track rack effects unit and several EQ modules. So it hasn’t changed much so far.

EP: I think, certainly with the They Were Dreaming They Were Stones record, it does come across that the effects processing is almost invisible. What comes over is the content, whatever it is you’re trying to communicate.

PM: I think another thing over time, as far as manipulation, the processing has been less to do with changing the sound itself and more to do with how the sound is used. More things like layering and delays or strata of the same sound, but without actually changing the quality. I mean, I recorded the sound because it was interesting to begin with…why would I want to lose the qualities of it? So just [working] with an EQ and certain effects of layering, in that instance, is mostly what I did. Most of the sounds, however much they’re cut and spliced and multiplied, are exactly how they sounded in the real world. Pretty much anything on that album.

EP: When you’re doing this layering, like for example the roar of jet engines next to the roar of a football crowd, are you looking for sonic similarities between the two things?

PM: I think I look for things that complement one another. So for instance, with that example, the drone of that airplane cabin was quite low and rumbly and grainy and airy in a way. And the football victory celebrations, which are actually not voices but car horns in a square in North London, a very Turkish neighbourhood, and after they won some match in whatever the last World Cup was, I sat in the park, it was in Newington Green in North London. I sat in the middle of the park and then the vehicles were just circling the green, and their cars in a big train circling, leaning on their horns the whole way! That’s what all those sounds were, which were very high-pitched and tonal, and the high-pitched tonal chorus of horns quite complemented the grainy rumble of the [cabin]. So it’s in listening to one sound and saying, well what’s going to bring out its qualities and what will it bring out the qualities of, and contrast well, without them becoming muddy. So that’s what I look for.

EP: Is the site and the precise instance where you made the recording important to you?

PM: That’s an interesting question, because up till now I’ve always insisted on including quite detailed notes, or at least including the specifics of what all the sounds are on the liner notes for the CD. That’s why, presumably, you know that they were football victory celebrations. On the one hand, what’s important to me about the sounds is their sonic quality, specifically. As far as listening to the sound, it’s not the context that interests me at all. In fact, I’m trying to remove them from those associations, and just present them as a sonic event that you can hear in its own right. But on the other hand, almost in support of that fact, and I think maybe on a more intellectual and less visceral level, I find it fascinating and really interesting to know after the fact where the origin of those sounds is. And also as an artist, to give that specific human link to the situation in which it was recorded. So when asked, I always say I prefer that somebody listen first and maybe listen several times, and maybe only once they know the piece really well, and have created their own context for it in their own mind, that they then go and read the liner notes, and have what I hope becomes a giddy pleasure in finding out. ‘Is that what that is?’ And some people find that contradictory that I do that, because if it doesn’t matter where the sound came from, then why do you need to write it down? But I think they really support one another. I mean the fact that it’s not at all what you expected really supports the fact that it doesn’t matter where it came from.

EP: You see Chris Watson, who I have a lot of respect for, as is well known is very scrupulous and meticulous about detailing where he captures every single recording. But that’s because, to him, it’s extremely important where and when they came from. He’s very much into this sense of place.

PM: But he also, I think, much more presents his work in a documentary fashion. Not to say that he doesn’t present it as his own art, but I’ve spoken to him about this as well, and I think the fact that it is more like a documentary photograph of a place, it is very important to know exactly where and when. And I love the fact that he gives time of day, all of that kind of measuring. Whereas with what I’m doing, I don’t at all feel that the soundscapes I’m creating are referential or documentary in any way. But I do feel that it’s important for me to present a personal link to the sound. I remember once somebody being very confused about the fact that there was a recording from the inside of a car vent, that was used in a composition. And I chose to list it as ‘air vent inside a red Austin mini’. And not only does the make of the car obviously not matter, but the colours! – But to me, it wasn’t at all irrelevant, the fact was that I was presenting my human link to where that sound came from. And to me that was very important. Not to map the sound within its human context, but present the sound within my human and artistic existence. Very personal, personal is what it always seems to me.

EP: When you just said that about Chris Watson, I thought maybe there’s a slightly more imaginative component to what you do.

PM: I think we’re just using sound differently, and our purposes are different. I’m in a way being more selfish, because I’m taking these sounds and saying I don’t care where they came from, I want to use them for my purposes. Whereas Chris is very much presenting them and saying, look at the amazing things that exist in the world. And I think that’s very noble. It’s fantastic.

EP: What other records have you issued?

PM: The one on Staalplaat, that was the first one. That was self-titled. There was another one on an Italian CDR label called S’Agita Recordings, which is curated by a couple called Paulo and Laura who have a project called Logoplasm together, which is fantastic…really recommend their work. That release was called Eyes Like A Fish. That was the second one. The third one was Definition, which was on Absurd. And then They Were Dreaming They Were Stones, which was on Ground Fault. The first 50 copies I think came with a three-inch CD called Elements. That’s it so far, that’s all the solo stuff. There are various compilation tracks.

EP: Do you have any views on being brought into the Ground Fault agenda…bracketed with these other musicians you may not have anything in common with, packaged in a similar way…

PM: I’ve thought about Ground Fault’s division system. In a way I kind of like the way Ground Fault does it, because it makes no concessions, it’s just 1, 2 or 3! It’s Quiet, Medium or Loud! They don’t try to get everything right. They say, these are the categories we have, and everything’s going to have to go in there somewhere. I don’t take it too seriously. In a way it’s good, because a lot of what he releases is unknown to anyone and it is good for me to be able to look at what he’s got out and personally…imagine I’m going to be more interested in the ‘ones’, maybe some of the ‘2’s, occasionally a ‘3’. I was also quite surprised to find my album was a ‘1’, because in my world it’s not particularly quiet! But when you hear some of his ‘3’s you can understand why it becomes a 1! As far as his packaging goes, he has this format where everything pretty much looks the same, but I also quite appreciate the fact that he also gives free rein over the inside of the booklet to the artist to do what they want. I know I’m not the first one to use that basically as an alternate cover. So my copies of that record are turned inside out. He’s a great guy, and I like a lot of what’s come out on that label.

EP: How long have you been doing your show on Resonance?

PM: Not quite since the very beginning. Resonance started in May of – God knows what year, 2002? And we started our show beginning of June. At first I was doing it with another guy called Joel Stern, who actually released a record with Michael Northam in the same Ground Fault batch. We did the show together for not quite a year, he then went back to Australia. He’s done stuff for the TwoThousandAnd label and he’s now co-curating a label called Naturestrip. The two CDs I have on Naturestrip are great. I haven’t heard the toshiya tsunoda one, the most recent one, but I’ve read the reviews. Originally the show was fortnightly, now doing almost weekly broadcasts. If there’s something specific I want to play, I ask [the label] for it. Most of it just gets sent to me. I write a pretty detailed playlist that gets around, even though many of them probably don’t get an opportunity to listen to the show, a lot of artists know that it’s there. So they send me things, and they certainly know about Resonance. As far as they’re concerned it’s a good place to get some exposure.

EP: I always say this, but what interests me about all the people you’ve named, and indeed lots of people working in this area, is how every single one of them can take a similar – or an identical – sound-source, and come up with something quite unique, which is uniquely their own. I’ve been sent a record by Jason Kahn from Switzerland, who has also used the sound inside an airplane cabin. It’s called Songs For Nicholas Ross on Rossbin. It punctuates these other sound episodes. I assume it’s him flying back and forth across the world, on his international jet-setting life, and his recordings of the cabin are quite different to your use of it.

PM: Well, I mean apart from two different artists using the sound differently, I’ll bet his airplane sounded very different from my airplane! I think it comes down to the personal aspect of it. Obviously, even if we all had [the same recording] – as often happens, people will exchange sounds – it always comes out different. In the same way that a hundred people with a trumpet will play a completely different song, a hundred different people with an airplane will come up with different recordings. It’s just a different kind of instrument.

EP: Do you ever do anything in a live context?

PM: Yes, I have done. I’ve played quite a lot of concerts and kind of gone back and forth between using just my field recordings, or trying to incorporate live sound sources, particularly when I’ve been performing within a theatre context, I’ve used more live sound sources and less pre-recorded sources. I’m at a point now where I’m less interested in continuing to just go on stage with a bunch of recordings and playing them back. I’m using raw field recordings that I’ll construct live, but don’t quite see the interest in that over listening to a CD. In the context of the diffusion of the electro-acoustic set and presenting it in its proper context with a proper audio system, I suppose I can appreciate simply doing a live playback. But also, coming from a theatre background, and as a live musician, I want there to be something special about a live concert. I want there to be something live about a live performance! I’ve been thinking about ways to incorporate live, found sounds and found objects; live field captures, in a way. Ultimately, in presenting things more in an installation context as opposed to a concert. I am definitely interested in doing an art gallery installation. That is something I’m just starting to really think about. It’s something that I hope to be doing within this next year [ie 2005].

EP: Do you have a visual component in mind that you would use?

PM: I have been working a lot with photographs lately. Still photographs. Might be trying to think of a way to work them together. I also have a plan with a painter friend of mine to do a collaborative gallery project. She does very abstract landscapes, but from very specific locations as an inspiration for them. Quite beautiful and vast. She actually approached me and asked if I’d be interested in doing some sort of sound and painting project, for a single painting and a single sound piece inspired by a specific location. I don’t know how that would be presented, but we’ll be working on that hopefully in the next year. [In art galleries], sound often seems to be coupled with video. Which I like less, I think. I find it really distracting. Putting up some random visuals while you’re playing a concert is something I never can fathom. So the idea of sound being coupled with a still image or an immobile structure may be something I’m more interested in. Something to meditate on I suppose. I quite appreciate Francisco López’s method of just giving you a face mask and turning out the lights! It works really well, with his material. You really are able to get lost in the sound, and that’s what I want from a live performance. Again, there’s certainly nothing live about [his method], he just hides himself away with two CD players, but he creates a context for it.

EP: Do you know John Grzinich?

PM: I don’t know John. I’ve had contact with him in the context of recordings for Framework. He’s a good friend of Michael’s, so I sort of feel I know him.

EP: There’s something quite metaphysical about what Michael Northam’s doing. It’s very hard to grasp. Even he himself can’t really articulate it fully.

PM: I think that’s the point. It’s not really articulable in language what Michael’s all about.

EP: I think the thing he shares in common with jgrzinich is there’s always some document happening which they try and document in sound, and it’s often a very strange event. I think they’ve even gone to the lengths of having some kind of ceremony performed with friends, almost like a musical improvisation, playing sticks and stones in the woods or something.

PM: What we have talked about that I most identify with in his work and my work, is Michael’s idea of time-stretching. Creating a suspension of time via music, for a listener. Again, it’s the same thing with Francisco and his face masks. Being able to listen to a piece and be removed from your current physical reality, really get immersed in it and lose yourself in it. Michael describes that as time-stretching. I can identify with that.

EP: But it’s not the studio meaning of time-stretching, which is where you extend a tape by use of varispeed.

PM: No, it’s a metaphysical meaning.

EP: I think where you have succeeded, with your new record, is in allowing the listener to hear the world anew. It’s sound that appears to be familiar, and yet it really does surprise the listener.

PM: I’ve been working a lot more lately with completely unmanipulated recordings. The last piece I’ve been working on is just had-edited on the minidisc player, raw recordings. It’s quite a different direction from everything I’ve done, but it shares those qualities of presenting these sounds out of their context and in a musical form.

EP: In terms of quantity of stuff that you have to listen to, in order to get to a finished product, and the time you spend listening to it, what would be the ratio of how much you have to gather and process to make one composition?

PM: Oh, it completely depends. Sometimes I might have one 3-minutes recording that’s so amazing that I can do a half-hour piece out of it. Or I might have a month’s worth of field recordings from Paris that have been cut down to a 14-minute piece. It depends on the sound itself, and it depends on how it ends up getting used. Sometimes I’ll take a recording that just demands to be used a certain way, and sometimes I’ll be working on a piece and I’ll want a sound that has a certain quality and I’ll have to go back to the archives and look for something. Certainly, it’s only a tiny fraction of my archives of recordings that have found their way into a composition. I must have about a hundred discs full of sound recordings and only a very small amount of them have made their way onto the four CDs. I’ve started to feel like I need to – somewhere deep in my mind I’m hesitant to continue making more recordings, because there’s so much that when I listen back to it, I think well, gotta use that! How have I not done anything with that? So I make new recordings and think, is that gonna just get lost in the pile? Which is silly, because of course at the same time I hear something I want I’m going to record it. But I do need to find the time to go back over five year’s worth of recordings and pull things out.

EP: Are you connected with the people who do the Phonographies CDRs?

PM: In a way. It’s a loose collective, and I’m part of the collective. They’re not based anywhere. It started out as a Yahoo group mailing list. There was a group called lower case sound online, and it was there many years ago that somebody suggested, because there was quite a large and specific activity of people interested in field recording amongst a wider circle of interests in the lower case group. And it was suggested that a field recording group be started and that’s how it happened. The person who has released the phonography,org compilations, Dale Lloyd, is in Seattle, He runs AND/OR records. The person who maintains the phonography,org website is somewhere in California, maybe San Francisco. And then the person who maintains the mailing list, he may actually be in San Francisco as well but the fact is the members are all over the world. And events have started happening in various places all over the world, there’s been events in Texas and in New York, in California and Seattle, and there are going to be some in Scotland, although nothing in London so far officially under the Phonography heading. I’ve been part of that since the group was first started, just on a participatory level, and involved in the compilations. I feel the same way about the Phonography discs that I feel about Chris Watson’s work, to a certain extent. I appreciate and I’m very interested in their documentary aspect, and not to remove any artistic intention from it, but they are presenting snapshots in time of sound. It’s the sort of amateur group to Chris Watson’s professional group, just as far as the technology that’s involved. It’s an opportunity for people to get things out. Some of it’s great. Some of the recordings I may find less fascinating than others, but for the most part I appreciate them. Those discs are what inspired me to be working on these Framework pieces. In presenting these raw recordings but in a more musically structured way, just through editing. They came directly out of listening to the Phonography compilations.